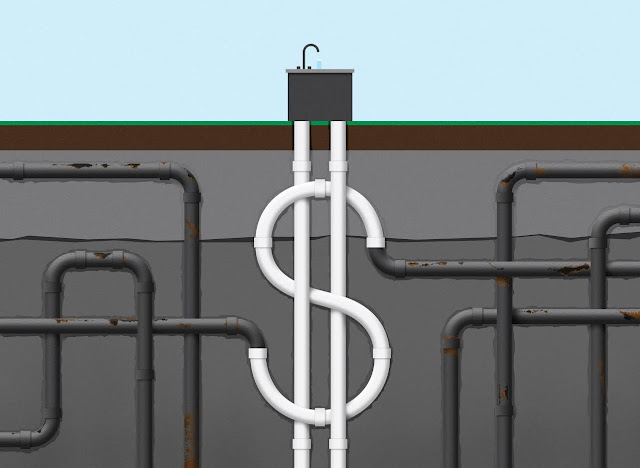

Fighting to replace U.S. water pipes:$300 billion war beneath the stree

America is facing a crisis over its crumbling water infrastructure, and fixing it will be a monumental and expensive task.

Two powerful industries, plastic and iron, are locked in a lobbying war over the estimated $300 billion that local governments will spend on water and sewer pipes over the next decade.

It is a battle of titans, raging just inches beneath our feet.

“Things are moving so fast,” said Reese Tisdale, president of water advisory firm Bluefield Research. And it’s a good thing, he says: “There are some pipes in the ground that are 150 years old.”

How the pipe wars play out — in Pittsburgh and countless other municipalities — will determine how drinking water is delivered to homes across the United States for generations to come.

Traditional materials like iron or steel make up almost two-thirds of existing municipal water pipe infrastructure. But over the next decade, as much as 80 percent of new municipal investment in water pipes could be spent on plastic pipes, Bluefield predicts.

The outcome of the rivalry will also determine the country’s response to an infrastructure challenge of epic proportions.

By 2020, the average age of the 1.6 million miles of water and sewer pipes in the United States will hit 45 years. Cast iron pipes in at least 600 towns and countries are more than a century old, according to industry estimates. And though Congress banned lead water pipes three decades ago, more than 10 million older ones remain, ready to leach lead and other contaminants into drinking water from something as simple as a change in water source.

Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority customers are set to pay nearly 50 percent more for service by 2020, a pricing surge meant to restore the city’s flagging water infrastructure.

In Flint, Mich., as many as 8,000 children were exposed to unsafe levels of lead after the city switched to a new water supply but failed to properly treat the water with chemicals to prevent its lead pipes from disintegrating. Corroding iron pipes, meanwhile, have been linked to two outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in Flint that added to the public health emergency.

The plastics industry has seized on the post-Flint fears.

The American Chemistry Council, a deep-pocketed trade association that lobbies for the plastics industry, has backed bills in at least five states — Michigan, Ohio, South Carolina, Indiana and Arkansas — that would require local governments to open up bids for municipal water projects to all suitable materials, including plastic. A council spokesman, Scott Openshaw, criticized the current bidding process in many localities as “virtual monopolies which waste taxpayer money, drive up costs and ultimately make it harder for states and municipalities to complete critical water infrastructure upgrades.”

Opponents of the industry-backed bills, including many municipal engineers, say they are a thinly veiled effort by the plastics industry to muscle aside traditional pipe suppliers.

“It’s simply catering to an industry that is trying to use legislation to gain market share,” Stephen Pangori of the American Council of Engineering Cos. testified this year before a Michigan Senate committee.

To more directly reach towns and counties across the country, the plastics industry is also leaning on the American City County Exchange, a new group that gives corporations extraordinary capacity to influence public policy at the city and county levels. The group operates under the auspices of the American Legislative Exchange Council, a wider effort funded by petrochemicals billionaires Charles and David Koch that has drawn scrutiny for helping corporations and local politicians write legislation behind closed doors.

Corporations pay membership fees as high as $25,000 to gain access to some 1,500 mayors and local council members who have signed up for the initiative. At a July convention in Denver that brought together about three dozen local legislators, Bruce Hollands, executive director of the plastic pipe industry group Uni-Bell PVC Pipe Association, discussed what had gone wrong in Flint, and explained what needed to be done to open up local bidding for plastic water pipes. To spur local decision-making, the ACCE has also adopted model legislation pushing for more open bidding for water pipes.

“We’re just trying to take up policies that limit the size of government, that keep it from growing exponentially,” said Jon Russell, national director of the ACCE and a councilman from the town of Culpeper, Va.

Plastics are an obvious replacement for the country’s aging pipes. Lightweight, easy to install, corrosion-free and up to 50 percent cheaper than iron, plastic pipes have already taken the place of copper as the preferred material for service lines that connect homes to municipal mains, as well as water pipes inside the home.

Still, some scientists warn that the rapid replacement of U.S. water infrastructure with plastic could bring its own health concerns.

Scientists are just starting to understand the effect of plastic on the quality and safety of drinking water, including what sort of chemicals can seep into the water from the pipes themselves, or from surrounding groundwater contamination. Studies have shown that toxic pollutants like benzene and toluene from spills and contaminated soil can permeate certain types of plastic pipes as they age. A 2013 review of research on leaching from plastic pipe identified more than 150 contaminants migrating from plastic pipes into drinking water.

“Plastics are being installed without any real understanding of what they’re doing to our drinking water,” said Andrew J. Whelton, assistant professor of civil engineering at Purdue University, and an author of the 2013 study. “We don’t know what chemicals we’re being exposed to.”

Sensing an opening, the iron pipe industry has started a public relations push of its own, voicing concerns over plastic, wooing President Donald Trump with accolades for his infrastructure drive, and setting up a war between the two industries.

“Iron is just more durable. It’s a more proven material,” said Patrick Hogan, president of the Ductile Iron Pipe Research Association, the industry’s main lobby group. “Iron’s been in the ground for 100 years.”

The uncertainty over potable water pipes of all kinds is exacerbated by a lack of regulation over their safety. There is no federal oversight of the materials or processes used to manufacture plastic water pipes; instead, water pipes are certified and tested by an organization paid for by industry.

That organization, NSF International, displays a picture of the Capitol building on its regulatory resources webpage and runs a hotline for questions on regulations and product safety. Yet it has never received regulatory authority from the federal government. Nor does it disclose test results for the pipes it certifies.

NSF International called its testing robust. “If a product does not meet the requirements of a standard, it will not pass,” said Dave Purkiss, the organization’s general manager of water systems.

Comments

Post a Comment